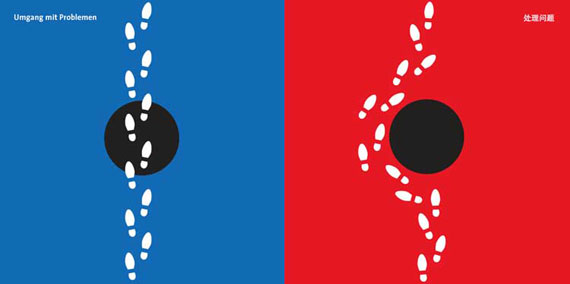

People think differently. Cultures think differently. Coming from a culture dominated by the traditions of Western philosophy and the scientific method, here is something that may be difficult to grasp: Logic is not universally viewed as being objective. And in some cultures, “logical thinking” just really isn’t very important.

This is something that frustrates many foreigners (from western countries) when they move to China. That frustration can mount with time and usually leads to one of two outcomes: the foreigner in question becomes immensely annoyed with China and its way of life, or makes a concerted effort to understand a way of thinking that does not rely on logic as we know it.

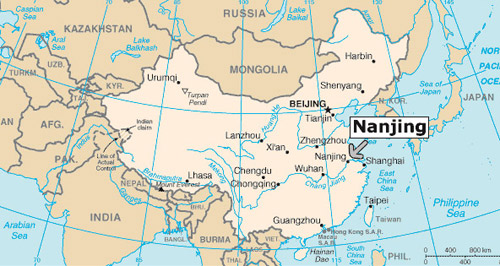

These ideas are the premise of “The Geography of Thought: How Asians and Westerners Think Differently… And Why” by Richard E. Nisbett. The author, who is a professor of psychology at the University of Michigan, argues that different ecologies, social structures and philosophical traditions dating to ancient Greece and China have influenced Western (in this book, defined as the United States, Canada, Europe and the British Commonwealth) and East Asian countries (China, Japan, South Korea) to the extent that people from those countries actually perceive and think about the world differently. Nisbett also relies on the results of several psychological experiments to argue that people from Western and East Asian countries sometimes have “profound” cognitive differences.

The easiest way to even try to summarize Nisbett’s argument is to go back to the (intellectual) beginning – the philosophical traditions of ancient Greece and ancient China.

The ancient Greeks – remember, the creators of democracy – had a sense of personal agency. They believed that every human being is a unique individual. In addition to that, the Greeks were curious about the world around them and took steps to study and categorize the natural world, creating scientific principles that could be used to understand nature. The Greeks’ belief in individualism and categorization fostered a tradition of oral debate that ultimately led to the creation of logic itself; Aristotle is even said to have worked out the rules of deductive logic because he was sick of hearing nonsensical arguments during public debates.

The goal of deductive logic is to use reason to reach a conclusion that is necessarily true. That conclusion is concrete, because it has been proved.

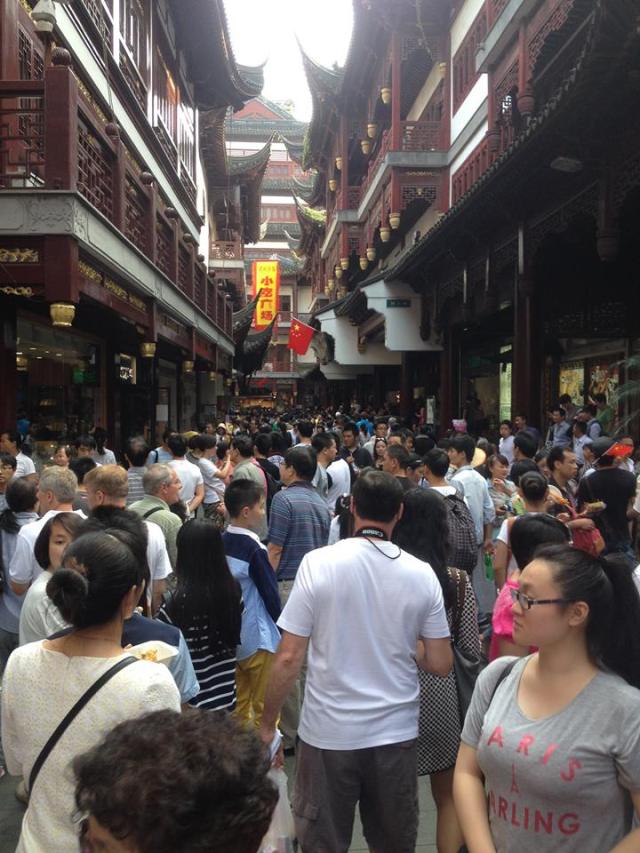

Ancient Chinese philosophy, a huge influence on Japanese and Korean culture, emphasized the importance of social harmony. Avoiding friction with family, friends and colleagues and living within a clan – such as a family or village – was the only way to coexist peacefully in Chinese society, where hierarchy determined everything. Confucianism, the chief moral philosophy in China, stressed the importance of familial and societal relationships (children- parents; younger siblings- older siblings; wives- husbands; subjects- emperor) that formed daily life. There was no room for personal agency; instead, Nisbett suggests the importance of mutual relationships created a sense of collective agency. And when you live your life in a society that champions social harmony, understanding the context of any given situation is key to survival.

Chinese philosophy was never influenced by deductive logic. The ancient Chinese did not believe in absolutes. Instead, they believed the world is constantly changing (hence the importance of context) and full of contradictions – what appears to be true now may be untrue later, and vice versa.

The influence of these philosophical traditions can be seen in their modern day heirs, Nisbett writes:

“The collective or interdependent nature of Asian society is consistent with Asians’ broad, contextual view of the world and their belief that events are highly complex and determined by many factors. The individualistic or independent nature of Western society seems consistent with the Western focus on particular objects in isolation from their context…. And the belief that they can know the rules governing objects and therefore can control the objects’ behavior.”

It’s easy to see where these different outlooks could clash – for example, contracts. In the Western world we tend to take contracts – whether for employment, housing or even a gym membership – quite seriously. When you sign on the dotted line, you are agreeing to honor the contracts terms and conditions as they are stated. No wiggle room here.

In East Asia (again, my own personal experience of this has only been in China) contracts can be more of a … suggestion. Yes, a contract is an agreement, but changing circumstances after the signing could potentially modify the terms of that agreement.

This can lead to some uncomfortable misunderstandings. Nisbett notes the example of the Japanese-Australian sugar contract dispute in the 1970s, when the East Asian emphasis on context came head to head with the Western emphasis on rules and order. In that case, Japanese sugar refineries agreed to provide Australian suppliers with sugar over a period of 5 years for $160 a ton. Shortly after the two parties signed the contracted agreement, the value of sugar on the world market plummeted. Due to the different circumstances, the Japanese asked for a renegotiation of the sugar contact. But to the Australians the signed contract was binding and therefore unchangeable, despite the altered context.

The point of this post isn’t for me to go on about philosophy and international business disagreements. The reason I’m writing about this is because I personally know how confusing and even annoying it can be to live in a culture where you cannot understand the accepted rationale for anything (Why won’t anyone in China ever tell you if there is a problem in the workplace? How is a person ever expected to improve if they are never presented with the problem in the first place?) and I’ve seen how it can foster resentment. In Shanghai I once witnessed my colleagues from European and American backgrounds asserting that Hong Kong should be GRATEFUL for British colonization because the British gave them “the gift of a civilized society”.

All of this was said in front of Chinese people who understood English. There was no shame, only sheer belief in Western cultural superiority.

It’s important to recognize that any culture is going to think that their way is the “right” way unless it’s been exposed to another way of thinking. Sometimes you have to question everything you’ve ever been taught about what is sensible or logical and admit that your way may not be the only way. That’s not easy.

Some social scientists believe we have reached “the end of history” and that capitalism, modernization and democracy will eventually dominate every country on the planet; others suggest that we are marching toward an unavoidable ultimate clash between the West and East (specifically the Islamic Middle East) due to irreconcilable differences in values. Nisbett, however, argues for a future of Eastern and Western convergence.

“If social practices, values, beliefs and scientific themes are to converge, then we can expect that differences in thought processes would also begin to evaporate,” he writes.

Meaning… peace on Earth? That would be nice.